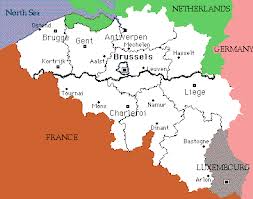

We are always told to keep out of other people’s politics but, as an admirer and a long-standing resident of this  country, I feel as concerned as a lot of Belgians do about all the talk of breaking the country up. Not that we did a very admirable job in putting it together in the first place. But, then, the things we foreigners – Brits, Germans, Dutchmen, Frenchmen, Austrians, Spaniards, Romans, etc. – managed to do to this little slice of Europe over the millennia don’t even bear thinking about…

country, I feel as concerned as a lot of Belgians do about all the talk of breaking the country up. Not that we did a very admirable job in putting it together in the first place. But, then, the things we foreigners – Brits, Germans, Dutchmen, Frenchmen, Austrians, Spaniards, Romans, etc. – managed to do to this little slice of Europe over the millennia don’t even bear thinking about…

History & Culture

The tussle today between the two main language communities (Dutch in the North; French in the South) has much to do with history, though many Belgians seem to be unaware of the fact. It also has to do with money (federal transfers from north to south), much more personal issues such as the encroachment of Brussels residents on the periphery (and here the international community is as much to blame as the Bruxellois themselves), and, unfortunately, simple prejudice and intolerance.

Few of the really big purported cases of cultural incompatibility have much to do with race or language. In the case of Bosnia-Herzegovina, it was not just a matter of different languages and religions. The indifference that soured into violence had, even more, to do with different lifestyles: the Bosniac Muslims were mainly townspeople while the Serbs were predominantly rural smallholders. So they had few affinities in a number of respects.

Something of the kind applies here in Belgium. The people of what was to become Belgium got on well enough until the 17th and 18th centuries when a French-speaking elite installed itself in the country’s big cities – not just Brussels, but such traditional centers of the Flemish culture as Bruges, Ghent, and Antwerp.

Superficially, the difference was one of language but, deep down, it was a matter of class. The French elite, which dominated much of life at the creation of the Belgian state, went out of its way to make Flemish speakers feel inferior. Those of the latter that then wanted to get upwardly mobile, and took the trouble to learn French, only made matters worse by turning against the rest.

It was only in 1873 that the Flemish were finally allowed to plead their case in court in their own language. Up to WWI, army orders were only given in French: the stories of Flemish foot soldiers dying because they couldn’t understand the commands of their officers may not be true, but the moral violence inflicted was just as destructive.

Business in Belgium

What expats should understand is that, other than language, the only real differences between the Dutch and French speakers are behavioral ones. I notice in particular that Flemish people like to get straight to the point, whereas Walloons tend to ramble on a bit. But it is a behavioral difference, and language is part of behavior too. There’s also another, but peripheral, problem: Flemish people tend to put all French speakers in the same pot, overlooking the behavioral differences between the Bruxellois and the Walloons.

The Academic Side

Studies by Professor Jan Kerkhofs of the KUL indeed show that a consensus exists on the fundamentals of life and that the Flemish and Walloons are closer together in their value judgments than either the Flemish are with the Dutch or the Walloons with the French.

Another Flemish observer is Professor Francis Heylighen of the VUB who says: “Though Flemish and Walloon cultures differ in several respects (as could be expected, the Flemish are closer to the more disciplined, Northern European, Germanic culture, and the Walloons to the more life-enjoying, Mediterranean, Latin culture), they have more things in common than most are willing to admit.”

Moreover, unlike Bosnia-Herzegovina, Belgium has witnessed the loss of not a single life to these longstanding social tensions. Essentially (and of course there are glaring exceptions as in any culture) the Belgians are a very fair and level-headed people.

Looking Ahead

Maybe we can take heart from a study just published by the KUL. A survey of the sense of affiliation of 14-year-old Flemish kids shows that they identify with Belgium first, with their commune next, and then with the Flemish Community or their province (the exception is Limburgers who put their commune first, followed by country, province and then Community). In all cases, identity with Europe comes last…

Belgians’ roots go very deep. ‘Community’ would not be a big issue – but for the politicians.

- Is England Part of Europe and Is Britain Part of Europe? - 30 June 2016

- The German Culture and German Humor - 6 January 2015

- Saint Nicholas, Turkey and the Garden Gnomes - 5 December 2013